This fantastic building was made to be a landmark. Construction took over thirty years, beginning in 1920 and not completed until 1953. Only 25 years after completion, it was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places.

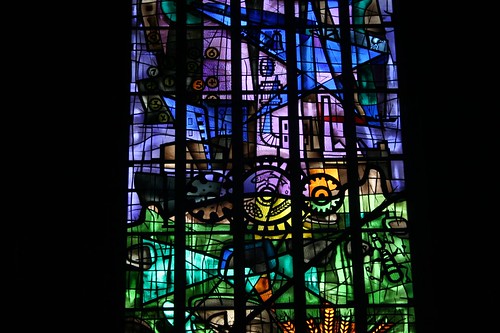

Architect Louis Bourgeois worked on the design for eight years. Though he strove to create a timeless style that incorporated symbolism from the world's major religions, you can take one look at his ornamental style and tell right away he was looking at the works of his contemporary, Louis Sullivan. Unsurprisingly, he worked in Sullivan's office in the late 1880s.

Gracefully overlapping curved forms evoke the idea of vegetation and geometry, all the while tautly bound within the confines of the building's surface. The lamp, by contrast, reveals the building's long period of assembly, spanning two architectural eras: it is pure MidCentury Modern.

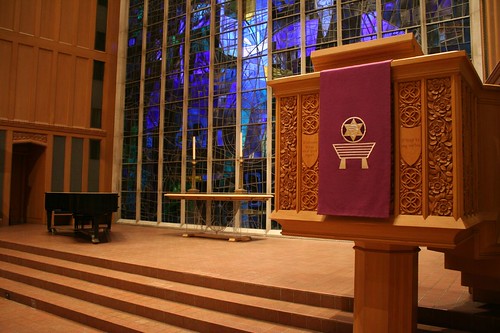

Likewise, columns on the periphery of the interior are utterly unadorned.

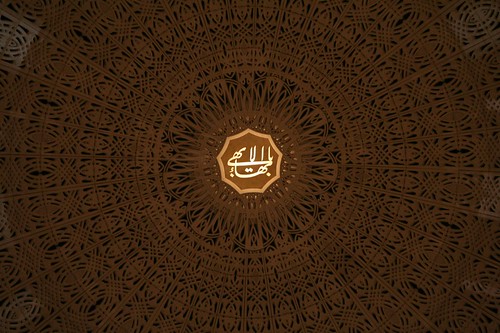

And what of that interior? What payoff awaits within that grand dome? Oh, it's worth it!

Your gaze is drawn up... and up.

The dome is beautiful by night...

But by day it truly and literally shines, as flecks of daylight slip in between the curving openwork of the dome.

Just how they constructed this magnificent trick remains a mystery to me.

This building shines gloriously by day or night, in all weather. Even in the dead of night, it casts warm light onto its surroundings.

The Bahá'í House of Worship is one of only seven such buildings currently in existence. They share with it several design concepts, such as the 9-sided circular design, a single open space within, a lack of any representational decoration, and a surrounding setting of gardens. The building is open daily, and if you arrive at the right time you might just have the whole magnificent space to yourself. It won't last, though, as a steady trickle of visitors comes to see this unparalleled marvel.