The colonnaded arcade and white coloration mark it as a product of the New Formalism, a short-lived 1960s Modernist style that found inspiration in the forms and proportions of Classical antiquity. Its most famous practitioners included Edward Durrell Stone and (for a time) Phillip Johnson, but it could be found in watered-down form across the new suburban landscape. Given its solid grounding in 1960s elegance, I dubbed it "Onassis Modern" long before I learned its proper name.

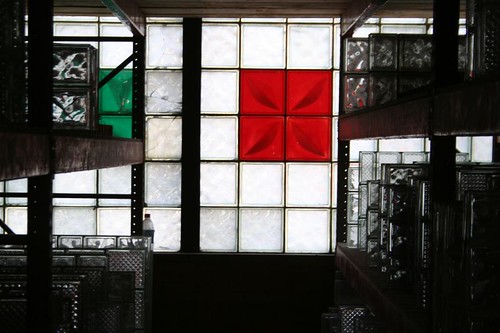

The polished white facades of New Formalism often proved to be empty promises, but this is a building that delivers. Behind those simple white columns rises two stories of faceted stained glass, wrapping the considerable length of the building, and telling the story of the Bible in blazing color and light. At some 23,000 square feet and 600 feet in length, is purported to be the largest installation of stained glass in the world. The wall was designed by the Conrad Pickel Studios; four years after design work began, its installation was completed in 1971.

The familiar scenes are there -- Adam and Eve in the Garden with the dinosaurs, the flood, Moses smashing the tablets, the Crucifixtion, and many more.

...wait. Dinosaurs?

The figures are impressive in their sheer number alone, but they also have a hypnotic element of the surreal. By the time the story reaches the modern era and the prophesies of end times, the subject matter has become truly and wonderfully bizarre.

When, for example, was the last time you saw a radio antenna rendered in stained glass?

How 'bout a satellite dish?

And so it continues: jet airliners, rocket ships. The subject matter leaves behind the typical church fare long before it reaches the climactic nuclear mushroom cloud.

The remainder of the interior pales before the allegorical onslaught of the walls, but still provides little gems of design here and there.

Like all mausoleums, there's a certain surreality to it, with solemnical design vying with homey lamps and couches in a bid to dominate the mood. Ultimately, however, it all pales before the unfathomably huge stained glass walls.

The cemetery itself is sparse, rural and vast, perhaps most notable for the deer that roam freely through its grounds and are hardly phased by humans walking right up to them.

Link: Resurrection Mausoleum official site