The building is unabashedly French Gothic on the outside, so it might come as a shock to find that it was completed in 1962, the very height of Chicago's MidCentury modern boom.

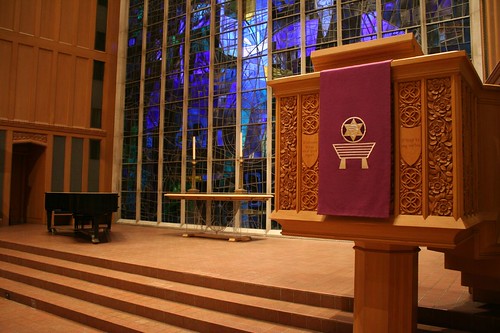

Inside, one finds a spatially grand but comparatively unremarkable interior, most notable for its conflicting personality. There is no lavish Gothic ornament, no encrusted decoration, no mind-blowing accumulations of sculpture or articulation. Unwilling to admit its modern heritage, the building seems a bit ashamed of its historicist clothing, unwilling to go whole-hog with the neo-Neo-Gothic. Amid the carved wood pointed arches and curlie-cues can be found anomalous touches of Modernism, such as the strips of faceted stained glass in the lobby wall.

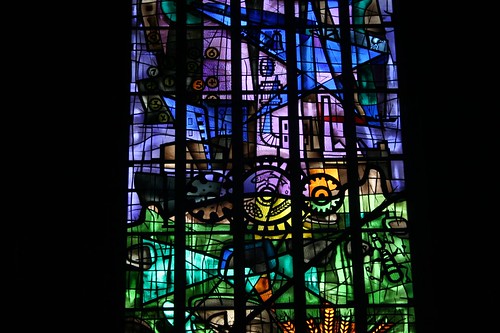

One thing does make the chapel truly exceptional, however, and it's staring you right in the face as you drive south on Sheridan Road. The stained glass windows are a masterpiece, and unlike any I've seen in Chicago.

I am an unabashed fan of the MidCentury work that came out of St. Louis's Emil Frei Studios. Their stable of artists created an interelated range of styles that took conventional Christian symbolism and broke it down, reinterpreted it, stirred it up, and let it explode onto window designs that are stunning portrayals of movement and feeling. By contrast, Chicago MidCentury stained glass is almost universally bold, bright, almost cartoonish, rarely abstract, and never subtle or ambiguous. I love it, make no mistake, but 1960s stained glass in Chicago is more likely to blow your mind through its enormity than its subtlety.

So it was a shock to walk into the Millar Chapel and discover that the brightly lit stained glass that motorists see on Sheridan was but a faint hint of what lay within (in fact, the front window's artistry is actually obscured by the glaring lighting, which leaves parts of the window relatively dark and the rest unnaturally overlit. Adding injury to insult, the window is not visible at all from the inside of the chapel.)

This was not some weak historicist brew, nor was it the usual Technicolor style of Chicago Modernism. This was artistry on a level to rival the Frei Studio at their peak.

Within those traditional Gothic window frames seethes a cauldron of imagery and color, muted reds and greens and blues swirling and blending. Recognizable faces and bodies and shapes rise out of an abstract mix of shapes and lines. At the top of one window, a smiling sun watches over the cosmos. In another, the head of a cow floats in a bubble. An owl perches, an atom spins, the US Capitol Building looms, and human figures rise and fall to meet their unspecified fates. The meanings are obscure, eliciting thought and curiosity.

The crowning glory is the rear wall of the chapel, where one of the building's rare Modernist conceits occurs. The entire rear wall is a window, top to bottom stained glass.

Unsurprisingly, these windows were not the work of a Chicago artist, but of internationally renown designer Benoit Gilsoul, Belgian-born and operating out of New York City. The windows were fabricated and installed by Chicago's Willett-Hauser Studios.

No comments:

Post a Comment