The city of Chicago exploded into the 1950s and 1960s. Thousands and thousands of houses and apartments rose up on the ever-expanding urban frontier, in a remarkably unified ensemble of styles. There's endless variation in the architectural details, but a great deal of it happens within a small range of fundamental building types.

The Bungalow/Ranch

Chicago's famous "Bungalow Belt" began rising before the World Wars, but didn't stop when the World Wars were over. The Bungalow simply cast off its original Craftsman-styled details and traded them in for MidCentury ones. Red-brown brick, stone lintels and quoins, Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired art glass, semi-octagonal bay windows, Spanish tile roofs, dormer windows and heavy eaves disappeared.

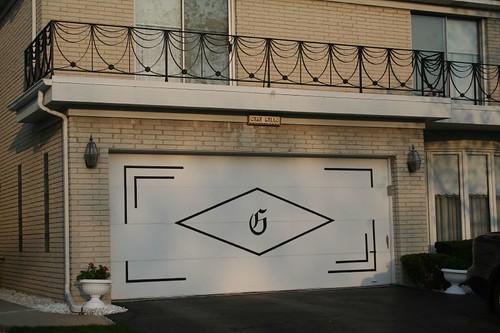

In their place came blond and orange brick, built-in planters, decorative wall panels of rough stone or elegant Roman brick, glass block, picture windows, geometrically designed front doors, patterned storm doors, and stylish door hardware.

These houses are compact and efficient, sitting tidily on a rectangular foundation, one story over a raised basement. The most classic style has a low-pitch roof with a hipped gable -- not quite the flat roof that High Modernism demanded, but a valiant attempt to minimize the roof's impact while maintaining the practical advantages of a pitched roof.

I'm honestly not even sure if "bungalow" is the right term for them. They certainly aren't ranch houses, however, and I've never seen the word "cottage" used to describe a Chicago house.

The Townhouse

The TownhouseAlso known as the rowhouse, the townhouse does exist in MidCentury garb, but it's not an easy housing type to spot in the wild. They're so unusual, in fact, that I hardly have any in my archives, and the ones I do have look more like they came from the Northwest woods than the northwest suburbs.

Townhouses consist of individual housing units sharing common side walls, but with no units above or below, and each with its own entrance. MidCentury versions are usually either one or two stories high (older versions go even higher), and are commonly arranged perpendicular to the street, with two rows facing a common courtyard.

The 3 Flat

The 3 FlatThe 3 Flat is a Chicago classic: three (sometimes 2 or 4) apartments vertically stacked, accessed by a stairwell on one side. Though there are plenty of pre-War examples, it's the MidCentury version that really codified the style and made it Chicago's own.

The standard version -- and there's hardly any example that isn't the standard version -- is two stories over basement. The basement may be a third apartment, or just a basement (that's the 2-flat version; the 4-flat version pretty much disappeared after World War 2.) Huge picture windows for each unit are requisite, projecting an image of clean, bright, modern spaces.

The stairs most often entered through a shared doorway, often under a little porch roof. Occasional variants will have two doorways. Endless decorative variety surrounds the doorway. I've seen planters, curved stairs, ornate ironwork in the railings and porch columns, glass block patterns, and an assortment of storm doors. And of course

the doors themselves were the canvas for some brilliantly creative carpenters. Solid angled walls sometimes surround the entry, in stone or brick, occasionally with light holes poked through them.

The stairway is most commonly illuminated by a large panel of glass block. Sometimes it's divided into strips. More rarely, colored blocks are used to create patterns. A handful feature sculpture panels in place of the glass block, favoring the outward appearance over natural light.

The 6-flat

The 6-flatThree-flats are generally long, narrow buildings, their short ends facing the street. For longer lots, the floor plan could be turned sideways and then mirrored, resulting in the 6-flat apartment building, two stacks of three apartments all sharing a common stairwell.

The 6-flat shares many decorative styles with the 3-flat. Perhaps the biggest difference is that the broad street-facing side walls of the 6-flat frequently become the canvas for decorative elements, such as stone panels and decorative lamps. The stairwell illumination panel became more creative as well -- colored glass block is more common on 6-flats, as are bottle glass and panels of translucent colored plastic.

6-flats were often paired with a mirror-image twin, both perpendicular to the street, with access from the street and alley via a pair of sidewalks.

3-flats often presented only a front facade to the street, with most of the building wrapped in cheaper Chicago common brick. 6-flats, with their entrances on the broad face, usually don't have that luxury; perhaps aided by the economy of scale, they often had much more extensive decoration than their smaller cousins.

The types pictured above are perhaps the most iconic Chicago style, but this flexible building type had several variants. A popular south side version features recessed balconies for each living unit, with the brick walls protruding from the body of the building to provide privacy, separation, and enclosure.

6-flats can have their broad or narrow faces against the street; the entry can be on or off the street in either configuration.

The X-flat

The X-flatJust as the 6-flat is a doubled 3-flat, so could additional units could be strung together to match the length of any lot, to make a 9- or 12- or whatever-number-you-want-flat building. The example below strings together three 6-flats for a total of 18 units.

On narrow lots perpendicular to the street, a small L-leg at the end of the lot could also provide additional floor area, closing off the block and creating a sort of half-courtyard.

A longer L-leg could give the unbuilt portion of the lot enough presence to hold a street corner, as on these Belmont Avenue-area 9-flats.

As with other types, mirroring the building could result in a court-yard like setting, such as this pair of 9-flats on S. Cottage Grove.

From the mirrored-pair, L-shaped X-flat, it's a short step to connect the two buildings, resulting in the courtyard building.

The courtyard walkupThe

courtyard apartment transcends architectural styles, being a common feature of every 20th Century Chicago landscape. In its MidCentury guise, it is essentially a series of 3- and 6-flats linked together by a connecting wing.

That wing could be a small extension of the corner apartments, or it could be a whole stack of 3 or 6 apartments with their own shared entrance.

They frequently feature balconies, which tend to be rare on their smaller counterparts.

The wings could be thickened up as well, essentially forming two 6-flats at the street.

The breezeway apartment

The breezeway apartmentI have no proof, but I strongly suspect this style was imported lock stock and barrel from California and Florida. Where else would it be considered a good idea to have the hallways on the outside?

These are essentially single-loaded corridor buildings -- a hallway with rooms on one side only. Instead of enclosing the hallway, however, it's left open to the elements, doubling as a porch and public gathering space. It's a great idea in mild climates. In Chicago, however... well, I have to wonder how much salt they have to dump on those walkways in the winter.

The stairwells are more sheltered, typically open only at their entrances; sometimes they have one or more doors. Their massive stone or brick faces are the usual points of decoration for the building.

Again, mirroring this long, thin style results in an enclosed courtyard. In the instance shown here, free-floating catwalks connect the breezeways of both buildings.

Beyond these types, the next step up is the Four-Plus-One, covered in careful detail over at

Forgotten Chicago. It's essentially a corridor/elevator building, floating over a covered parking area.

There are other types as well: split-level ranches, "flying-wing" roof single families, and taller elevator/corridor buildings. These types, however, tend not to share the common design vocabulary of the flats and bungalows, making them more distant cousins of the types listed here, and not as distinctively native to Chicago.