From the downtown intersection of Clark and Madison, you're within a two minute walk of a Catholic church, a Protestant church, and a Jewish synagogue. And all three are well worth the visit.

First United Methodist Church (The Chicago Temple)

The

Chicago Temple is the tallest church building in the world, and the only skyscraper in Chicago with a religious spire. It's a 1922 design by architects Holabird & Roche, in a French Gothic style. When it opened in 1924, it was the city's tallest building.

At ground level, the wood-lined main sanctuary is open for most or all of the day; you can wander in just about any time for a look. (Being downtown, that means there's sometimes a few homeless folks hanging out in the colder months, though the forbidding entrance lobby with its security guard makes it a bit uninviting.)

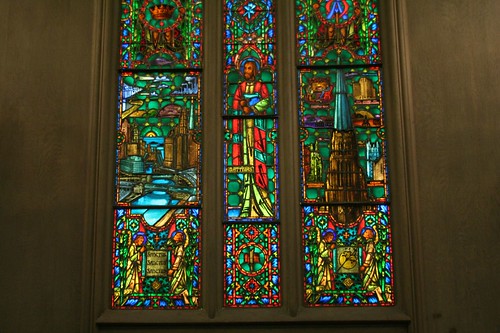

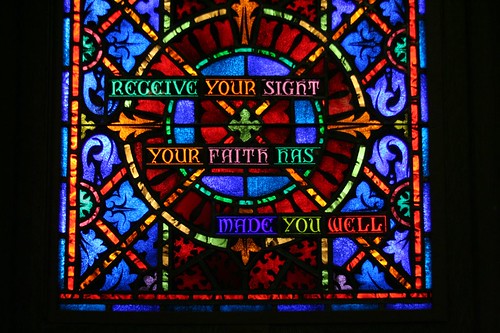

Those stained glass windows are an illusion - there's no trace of them on the outside of the building, and they remain brightly illuminated day and night.

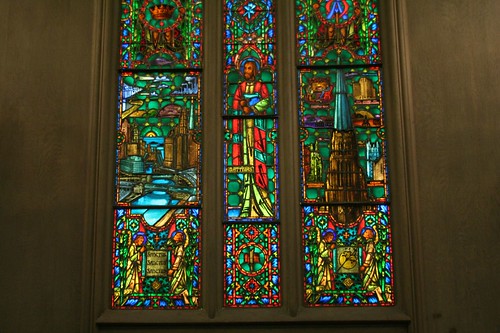

The stained glass is done in a traditional style, but with some contemporary subject matter, including Jesus blessing the skyline of the city and the highrise itself.

The sanctuary reaches some impressive heights, particularly when you consider the load of an entire skyscraper is carried above it.

But those heights pale compare to those of the Sky Chapel, just below the spire.

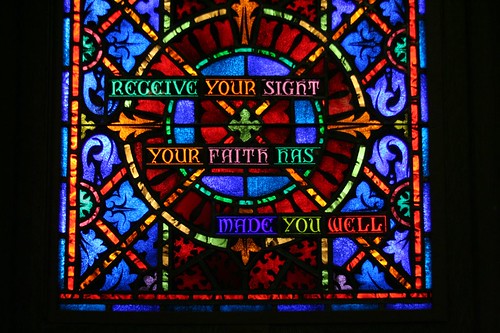

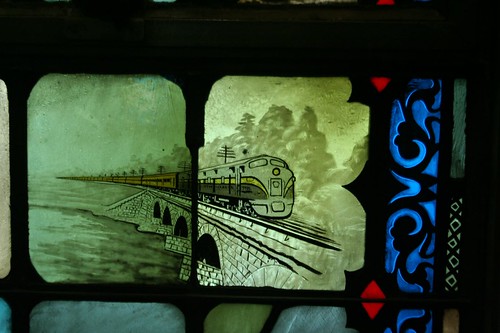

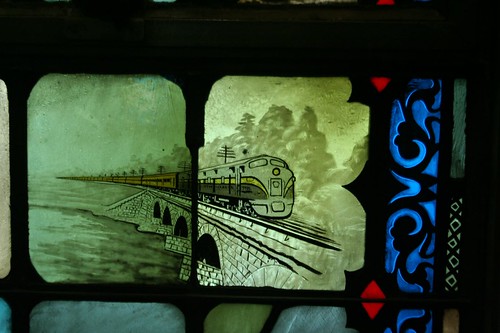

Long-planned, the chapel wasn't fitted out until 1952, when a bequest by the widow of the founder of the Walgreens chain made it possible. Despite the changing times, the chapel is fairly conservative in style - though the stained glass continues the theme of bizarre subject matter begun in the sanctuary below.

And once again, just in case you forget where you are...

Chicago Loop Synagogue

This Midcentury confection is slotted neatly into the street wall. Designed by architects

Loebl, Schlossman and Benett in 1957, the

Loop Synagogue opened its doors in 1958. The building is adorned by a 1969 sculpture entitled "The Hands of Peace" on the outside, by sculptor Henri Azaz, with stylized hands against a background of Hebrew and English letters spelling out a traditional Jewish prayer.

There's a sort of slow, deliberative elegance to this building. You can almost feel the architects pausing contemplatively, stroking their chins in thought perhaps, before finally selecting these wonderful huge wood door paddles.

Beyond those doors lies a simple passageway with offices and other spaces. The main worship space is on the second story.

The beautiful wall of stained glass was designed by American artist Abraham Rattner and installed in 1960. Based on the "let there be light" Torah passage, it depicts an abstract, metaphysical cosmos flecked with ancient Hebrew symbols.

The rest of the space is spare and clean, befitting its Modernist origins.

St. Peter's Church

Wedged between two adjoining buildings,

St. Peters Catholic Church gives the impression that it was carved out from a solid rock face. Solid, planar walls contrast startlingly with deeply hewn entrances and window openings, creating one of the best facades in the city. Unlike the contemporaneous

Queen of Heaven mausoleum, this 1953 church (architects: Vitzhum and Burns) shows a mix of modern and historical influences.

A three-story high crucafix by Austrian sculptor Arvid Strauss completes this compelling composition.

Like the Chicago Temple, the doors of St. Peter's are always open (again, meaning there's usually a few homeless guys hanging around, along with a smattering of curious tourists and the usual downtown office workers.) The space inside is vast, befitting the epic facade outside. Seemingly every surface is gleaming polished stone.

Deprived of natural light, the designers had to turn to other tricks to give the space a sense of holiness. Illuminated sculpture niches serve in place of stained glass windows, portraying the life of St. Francis of Assisi.

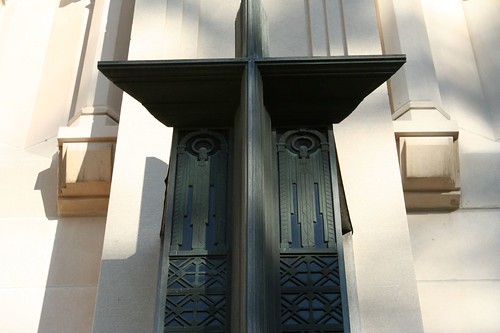

The building's lobby is notable primarily for its wonderfully ornate doors.

If you've walked past this place, take five minutes to duck inside. It's well worth the time.

A history of the church from Heavenly City at Google Books.

A history of the church from Heavenly City at Google Books.