St. John's is one of those pesky buildings that, today, is so obscured by trees and greenery that it's hard to get a photograph of the entire building. This is about the best I could do:

Inside, it's all vertical, though some basic Stade elements remain, such as an altered rendition of Stade's random cathedral glass, and those magnificent laminate wood beams.

As usual, Stade eschews most traditional ornament, but still decorates the space, using a celestial cosmos of floating globe lamps. The space is impressive by itself, but it's the globe lamps that really put it over the top, transforming it into a superb artistic work and also a fine representative building of its era.

Stade didn't do a lot of buildings entirely in brick, but here he shows a clear appreciation for the medium. Grids and rows of bricks project or recess, creating patterns in the wall. He uses randomly placed clinker bricks as wall decoration both inside and out. They give a human quality to these otherwise towering brick walls.

Even the cornerstone reflects the tall, boxy nature of the building.

Art within the church favors a sort of floating, variable-size font:

The Chicago Tribune of the era, which frequently profiled new Modern-style churches, is strangely silent about this one; thus I have no idea who the artist was.

Outside, a small projecting chapel wing reaches out to the west, at right angles to the main building; together, they form a small plaza space.

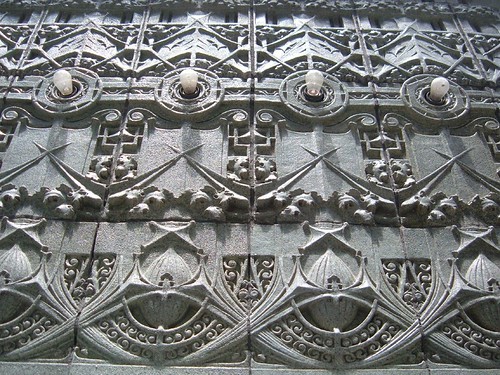

You might be shocked to find this view on the south-facing alley side of the chapel:

Turns out, Stade's design simply engulfed the 1953 chapel that was already on the site. What remains of the chapel's original skin appears to be a done timid, watery Gothic style; it was reskinned to work with Stade's vision. It doesn't seem like much of a loss, considering what we got in return.