The great Chicago Fire of 1871 was a watershed moment for the city. Beyond obliterating much of the city and triggering an architectural golden era, it also resulted in the city requiring brick construction within its limits. Thousands of brick buildings went up in the decades that followed, giving the Chicago cityscape its distinctive style.

Northside United Pentecostal Church - Andersonville

Northside United Pentecostal Church - AndersonvilleOutside the city, however, other communities were growing. Suburban areas like Ravenswood and Lakeview would eventually be annexed by their burgeoning neighbor... but not before they erected a number of churches that, unlike their Chicago cousins, could still be built of wood.

Resurrection Covenant Church - North Center

Resurrection Covenant Church - North CenterA number of these older buildings dot the Ravenswood area. One is a landmark. Others are less well known, and evoke the feeling of a small town church, something you'd expect to find a stone's throw from farmers' fields. Mostly they are simple in style, lacking elaborate detailing, substituting plain cathedral glass for stained glass designs or just dispensing with the whole colored window thing altogether.

Christian Community Church - Ravenswood

Christian Community Church - RavenswoodBelow are a few that I've explored in more detail:

Summerdale Community Church - 1892Originally Summerdale Congregational Church, if the stained glass transom window is any indication.

Addison Street Community Church

Addison Street Community ChurchAs simple as a country church, with handsome dark wood beams holding up the ceiling. Simple frosted, yellow-tinted windows give the space an otherworldly glow.

All Saints Episcopal Church - 1883

All Saints Episcopal Church - 1883All Saints is a landmark building, a rare Chicago example of Stick Style design. Designed by architect John C. Cochrane, the AIA Guide to Chicago notes that it's probably the oldest wood frame church in the city. The building is having its share of troubles today; if I'm remembering right, the tower and front porch are pulling away from the rest of the building.

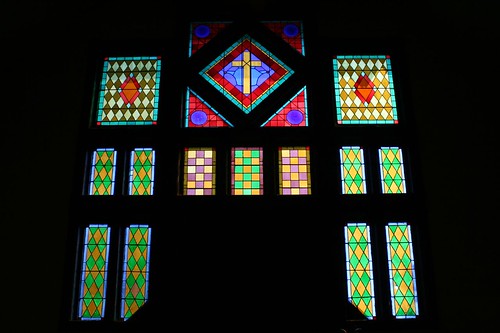

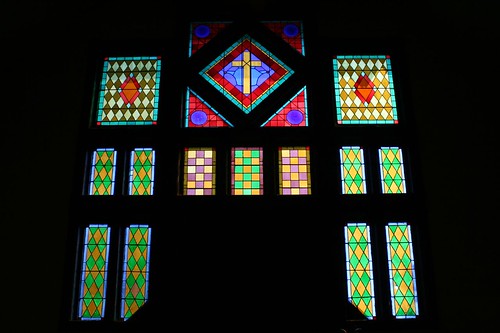

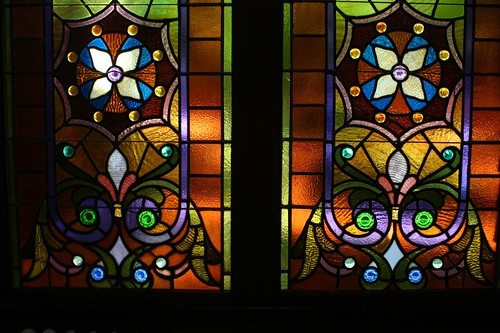

The windows make use of simple materials to create complex patterns; colored cathedral glass is arranged in diamond patterns to create walls of color. Combined with the lovely structural elements and the overall composition of space, this is perhaps the most architecturally satisfying of the bunch.

Lake View Presbyterian Church - 1888

Lake View Presbyterian Church - 1888If All Saints Episcopal is the queen of the wood frame churches, then Lake View Presbyterian is the king. Built in an equally rare Shingle Style, this landmark near Wrigleyville is jammed tightly into an urban site. The interior disappoints on some levels; it is sparsely ornamented, and an 1890 addition changed the orientation of the sanctuary, leaving an oddly structured space that is somewhat at odds with itself.

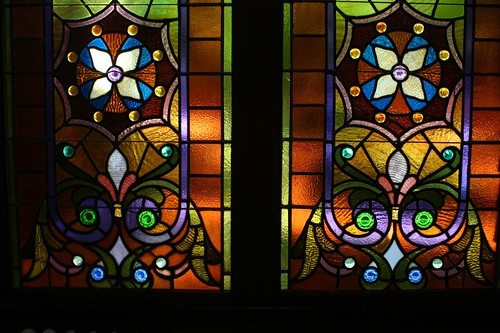

However, all is forgiven once you've seen the sun shine through the building's jeweled stained glass windows.

Lake View Presbyterian may also be the most heavily used of these churches; the day of my visit, a table with snacks and refreshments had lured a large crowd, that was still lingering and socializing a good 30 minutes after the serviced ended.