My interest in historic preservation comes from some fairly simple origins: namely, I have seen far too many beautiful buildings torn down. I see it and I am outraged, because I know we cannot and will not ever build such things again. They cannot be replaced.

"Historic preservation" is a double misnomer, for me personally. I'm rarely interested in buildings as an embodiment of a specific history. If history gives further ammunition for the conservation of a beautiful building, then so be it; but what I'm really and truly interested in is creating and maintaining beautiful urban places. And I don't want to see buildings preserved - locked in amber - but put to new and productive uses. Too often I feel that preservationists looking to save a building float pie-in-the-sky notions of museums, community centers, and other non-enterprises that cost money instead of generating it. I want old buildings to be living parts of the current and future economy.

Lately, over the last year or so, I've often felt a growing sense of helplessness and hopelessness over the fates of countless minor buildings and forgotten neighborhoods, places left behind by the vagaries of progress. I try to envision a future that would return life to these buildings. Amid a struggling economy, a global economic downturn, rising competition from overseas, and an American culture that is both increasingly insular and wracked with paranoid fears over its physical safety, I cannot do it.

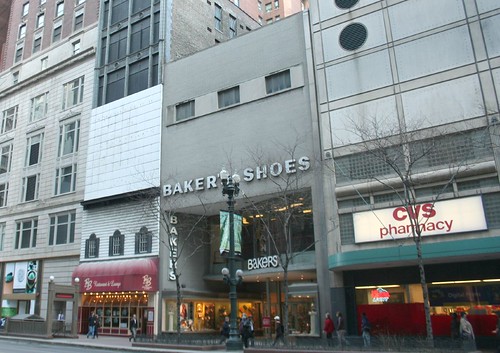

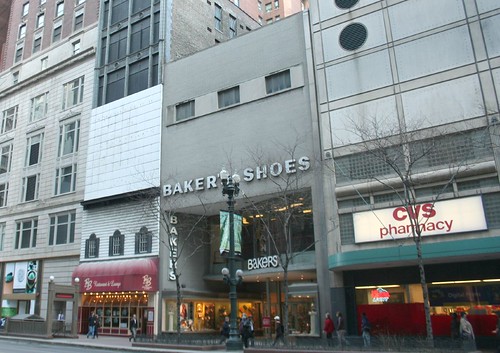

If you use Bing.com to take a virtual flight over older city neighborhoods, you'll see a pattern of scale. Everything we build today is gigantic. Gigantic schools go into old neighborhoods, and they're surrounded by tiny little houses on tiny lots. Goliath size vs. fine grain. The notion of acceptable size in America has inflated to the point of ludicrousness. I try to envision a modern chain store adapting to the fine-grained construction of the historic city - a Wal-Mart inserting itself into a dozen side-by-side storefronts. It's a nice fantasy, but try to sell it to corporate reps who are beholden to a particular development model.

It is a sad fact, little recognized but indisputable, that construction is the province of the wealthy. It takes serious money to build or renovate something, even with a heavy investment of sweat equity. And so the poor, or those of simply less-than-average means, wind up with the leftovers and the off-castings of the above-average. Today this means that the jobless are stranded in neighborhoods like this. Tomorrow it might mean that they are living in deteriorating suburban ranch houses. But neither bodes well for the future of surviving buildings in collapsing neighborhoods.

These problems are all interrelated. Overmassive scale, awful places, nemployment, sluggish economy, beauty allowed to rot, people left behind. If all the effort we've expended in the last 60 years in flinging ourselves further and further apart from one another were instead redirected into building up our cities as the dense, beautiful, walkable, humane places they once were on track to becoming, we'd all be better off.