"Every visitor says these are Chicago's most beautiful and unusual town homes." - August 7, 1957 Chicago Tribune classified ad

Midcentury builder Alvin M. Hoffberg brought a unique twist on the townhouse to Chicagoland in the 1950s. The Midcentury townhouse is a rare beast indeed, but it does exist, and Hoffberg planted several variations on a similar theme in Rogers Park and Evanston. He developed a series of one-story rowhouses ranged around a long, narrow courtyard.

Several decorative features make it obvious that these buildings are all by the same builder, but it was a classified ad for 1338 Main Street, shown above, that finally gave me the builder's name.

(Just so we're all on the same footing - a townhouse, in US parlance at least, is the same thing as a rowhouse - an individual dwelling unit that shares party walls on at least one side with another home, but has its own individual entrance at the ground. In the 1950s, "townhouse" probably would have sounded much more cosmopolitan and appealing than "rowhouse", with its connotations of crowded cities and industrial workers' housing.)

1338 Main Street shows up in a delightful little classified ad in the 1954

Tribune, advertised as a group of California-styled ranch townhouses:

"Very de luxe [sic] and unusual, on 1 floor, with full basement and roofed patio. Landscaped and decorated to suit. Tiled Youngstown kitchen, colored fixtures in tiled dual bath. Ample cabinets and wardrobes, many other features. Carpeting, utilities and rumpus room opposite. Fine residential area, close to all transporation, shops, schools and recreation."

Hoffberg went on to use this design in several more locations around Evanston and the far north end of Chicago.

239-45 Custer (Evanston) appears in the classifieds by 1963. Unlike the Main Street group, they're built over a raised basement, which also raises up the courtyard - an extra measure of privacy and separation from the street.

This design pops up several more times around the neighborhood, such as 135 Callan:

135 Callan, Evanston

135 Callan, EvanstonThese were advertised as 5-room townhouses, approaching completion in 1955 with prices ranging from $180 to $195 a month:

"For discriminating people who desire the utmost beauty, privacy and comfort, each a complete de luxe home in a choice residential area clos to shops, express "L", bus and train. Spacious rooms, huge wardrobes, snak bar, dispolsa, and de luxe utilities area few features."

7374-80 and 7382-88 Winchester, named "Park Terrace", stands in Chicago's city limits. Like the Main Street group, 7376 Winchester was advertised in 1959 with an emphasis on its fabulous rumpus room. Alvin M. Hoffberg, builder could be contacted at 6131 N. Sheridan.

A variation on these designs stands nearby in northern Rogers Park, marked by an entry gateway.

This is 7323-29 Damen (or maybe just 7327 N. Damen); at any rate, it's the Park Damen Town Homes. A resident of this site died in 1958; I have to wonder if his home was sold to make way for this building, which a

real estate agent lists with a 1960 date of construction (CityNews says 1957, but they can be real wonky sometimes.)

This group has a twin to the east, the Park Patio at 7342-44 and 7346-48 Winchester (where, perhaps not coincidentally, another owner died in 1960.)

Not only does it have the same sloped bay windows as the wood-siding buildings, it's got the same little cutesy development name in the same kind of cutesy font as the Park Terrace up the street.

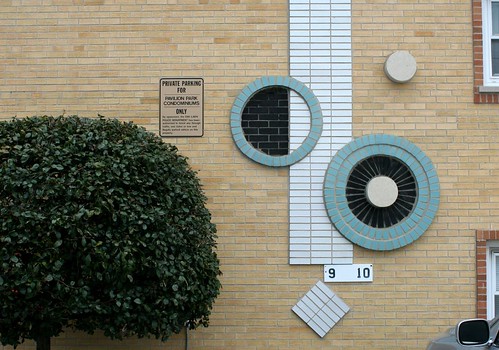

Hoffberg drew on a very distinct vocabulary of design ideas and facade materials: Flat roofs; picture windows set in square, boxed-out projecting bays or sloping walls, finished in wood siding and usually painted red or brown; rough-faced limestone banding at the windows; small patches of red Roman brick or flagstone; blonde brick.

Hoffberg had a second design, seen above, that was useful for narrower or shallower sites, consisting of a simple twin or duplex design - two houses, 1 party wall. 729-31 Brummel Street, above, is a typical example. The building opened in 1956.

Here's a virtual duplicate at 738-40 Mulford Street:

And another near-duplicate at 238-40 Custer, across the street from one of the courtyard townhouses. This one opened in September 1960, and was constructed by Elston Builders.

And here's the same idea again at 806-08 Mulford Street:

A third variation is a bit more free-form, with no courtyards.

244 Elmwood at Mulford Evanston - appears to have been standing by 1959; possibly by 1956.

700-706 Shaw

Both of these occupy corner sites and are paired with a duplex building, apparently a response to a square site.

"Distinctive 5 room apartments with a distinctive address built for discrminating tastes" -- Tribune classifieds, 1955

Like most developers from the 1950s and 1960s, Alvin Hoffberg wasn't exactly a celebrity figure, so there's not a lot of info about him. Mr. Hoffberg shows up in 1947 as VP and general manager of Leonard W. Besinger & Associates, Inc., working on a group of homes in Park Ridge (bounded by Devon / Talcott / Cumberland / Glenlake / Vine), designed by architects Marin J. Green and William Kotek. Then came his run of indepdent buildings in the mid-1950s. And then, poof, nothing. Silence. Whatever became of Mr. Hoffberg, he didn't make any more headlines after the early 1960s.

There are some other buildings in the area that share similar materials, particularly that rough limestone trim and red Roman brick combo, and some indications that Hoffberg worked with a few other companies.

314-16 Callen, for example is a co-op apartment building that dates to 1954, was put up by the Town Development Co., and was advertised using his distinctive vocabulary.

And 1601-09 W. Lunt, dating from 1964, is credited to Bannon-O'Donnel (realtors or builders, it's not clear), but has all the hallmarks of a Hoffberg design.

And these buildings are right across the street from the Elmwood/Mulford group, and use the exact same materials.

301 Elmwood, Evanston

301 Elmwood, Evanston 300 Sherman, Evanston

300 Sherman, Evanston 301 Elmwood detail...

301 Elmwood detail... ....and a detail from a known Hoffberg design across the street.

....and a detail from a known Hoffberg design across the street. "Sensationally different - California one story - designed in the modern trend, for discrminating couples" - Chicago Tribune classified ad, 1955